The narrative begins in a middle-class Jewish family, where two young sisters share a deep, intimate bond. The elder sister, who identifies as a lesbian, finds herself in a tumultuous conflict with their parents. Unable to defend her identity and unwilling to conform, she adopts silence as a form of rebellion, remaining mute for a year and a half. In response to the growing whispers and stigma from society, her parents commit her to a sanatorium. Ultimately, she makes the tragic decision to end her life by lying on the train tracks. She was 18 years old; her younger sister was just 11.

“That’s when I began planning my escape. I believed it was the only way I could survive.”

The parents sought to conceal the reality of their elder daughter’s suicide, while psychiatrists warned them that the younger daughter might follow the same path. At 14, she ran away from home, embarking on a life marked by drifting through various foster homes.

This younger sister, who endured profound pain from such an early age, would later become the celebrated American photographer Nan Goldin. Yet, the hardships of her life did not diminish as time went on. After leaving home, she spent a period in near silence, traumatized by her sister’s death. She became deeply introverted, grappling with social anxiety. At 15, she discovered photography, a passion that led her to settle in Provincetown, a Cape Cod community known for its LGBTQ+ residents, where she lived among other young people marginalized by mainstream American society.

“Photography was my only language back then. Suddenly, I had a voice, and I used it to express myself.”

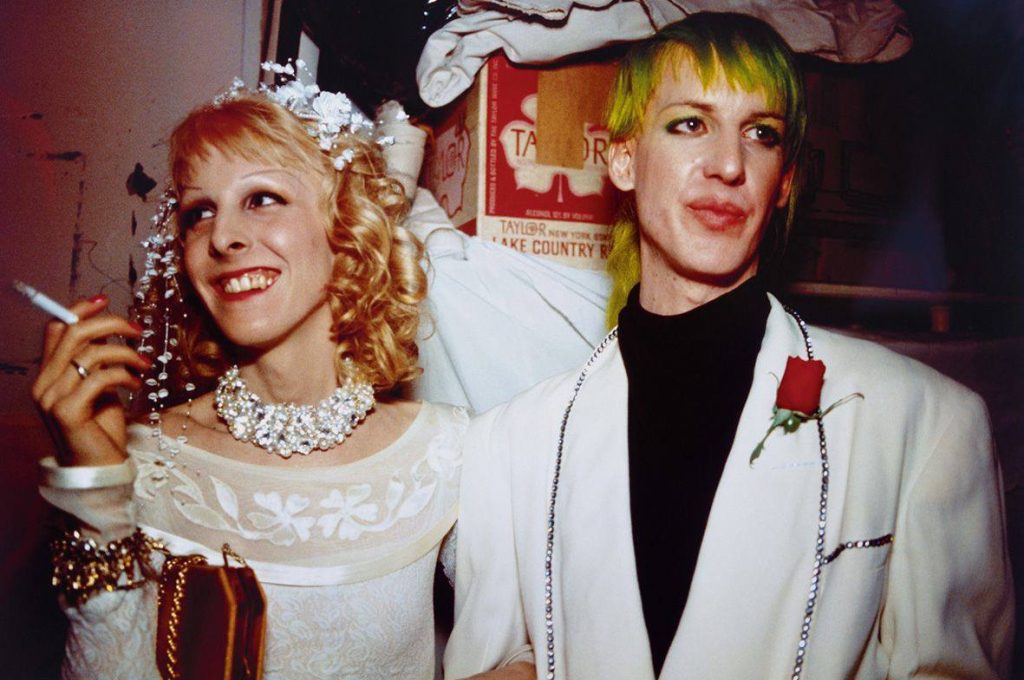

Photography became her diary, her lens capturing the lives of her friends: primarily those from the LGBTQ+ community. Her work explored themes of queer identity, AIDS, addiction, and intimate relationships: sex, love, life, death. The wild, seemingly immoral lifestyles she depicted were simply reflections of her reality. Unlike traditional documentary photography, her work carried no judgment or moral commentary akin to a Pulitzer piece. “When I was photographing them dancing, I was dancing too, when they were making love, so was I, or when they were drinking, I was drinking too. While photographing, there was no separation between them and me.” Goldin was deeply connected with her subjects, capturing both the beauty and fragility of their lives.

“Every time I faced trauma, I survived by taking photographs.”

For Goldin, photography was a method of healing, but at the time, neither her work nor her identity as a photographer was widely accepted. It’s crucial to remember that the 1970s and 1980s in America were times of harsh repression of queer culture, and women artists had little to no recognition. Goldin had to rely on underground bars to showcase her work through slide projections. To sustain her artistic practice, she even worked as a sex worker during her early years.

In the late 1980s, as AIDS ravaged communities, her seminal work, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, documented the lives of friends who succumbed to drug overdoses. Photography served as both her salvation and a record of everything she had lost. “I always thought that if I kept photographing certain people regularly, I’d never lose them. But my photos are all evidence of what I’ve lost.” The more she tried to hold on, the more she lost. As her work gained recognition, Goldin herself became deeply entangled in drug addiction. After a brutal assault by a boyfriend that nearly cost her an eye, she barely survived. Yet even in that moment, with her face bruised, her nose swollen, and her hair disheveled, she picked up her camera and captured what would later become an iconic self-portrait.

“I started with just three pills, but it escalated to 18, and eventually, I even began inhaling the drug.”

If you struggle to relate to the younger Goldin’s lifestyle (not that she ever sought anyone’s approval), perhaps her more recent actions will resonate. In 2014, after injuring her wrist, Goldin became severely addicted to the painkillers prescribed during her treatment. An investigation revealed that Purdue Pharma, the manufacturer of the highly addictive opioid OxyContin, had profited immensely from the drug, contributing to the deaths of 500,000 people. In 2017, she founded the activist group P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now), using performance art to protest and advocate for issues related to drug addiction.

Living through pain, creating through torment

Goldin’s life has been a continuous confrontation with the pain of loss. Must art always be intertwined with trauma? It’s hard to say. Although the photos she takes often end up as mere records of what has been lost, she has learned to face her trauma with courage, and in doing so, has transcended it, imbuing her life’s hardships with new meaning.

In a recent interview, she reflected: “At my age, you suddenly come face to face with death. I live in a loft apartment, I have my cat, and I go to the park to feed the birds. I am a perfect cliché. And I’m very proud of it.”

Photo Source: The New York Times, Marian Goodman Gallery, moom bookshop